Post by psuhistory on Jul 5, 2013 8:36:43 GMT -5

Team photo of Cincinnati's first championship club (96-44 regular season; 5-3 World Series): this is what baseball style looks like. Among the qualities lost in the media excitement over the White Sox' offensive power before the Series was the superiority of the Reds' relief pitching, especially that of the Cuban-born Dolf Luque (front row, second from left), who pitched 106 innings in 1919, mostly in relief (2.63 era, 1.179 whip). During the Series, Luque would pitch 5 innings of 1-hit, scoreless relief (6 ks, 0.200 whip).

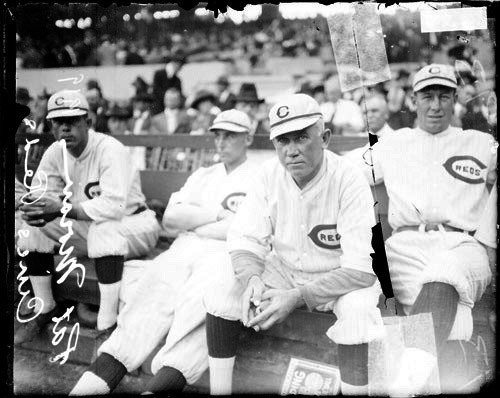

Manager Pat Moran on the bench at Redland Field, 1919, with (left to right) Rariden, Roush, and Greasy Neale (?), the right fielder. Moran ranks sixth among Reds managers in wins (425-329, .564). He followed the pattern of catchers becoming managers and had a knack for developing pitching staffs (for the Phillies as well as the Reds) at a time when managers did much of the work of general managers. His decisions to claim Sallee and Fisher on waivers from the Giants and Yankees, respectively, would pay dividends during the 1919 season. Above .500 over 4 of the 5 seasons (1919-1923) before his premature death at 48 in 1924, his strong teams finished second to loaded New York Giants clubs in 1922 and 1923.

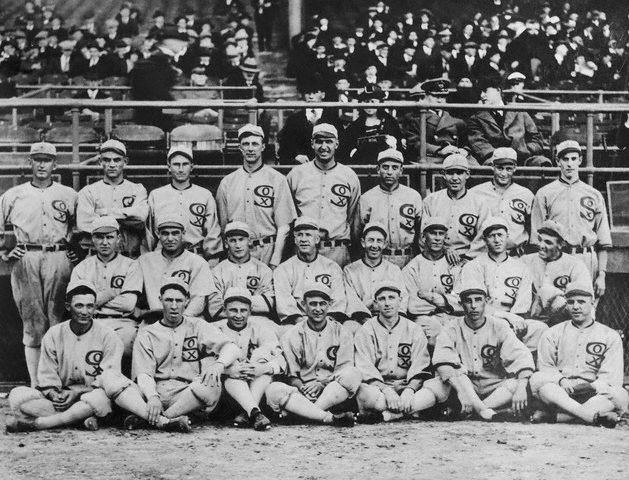

Chicago White Sox, 1919 (88-52 regular season): back row, left to right, Jackson, Gandil, McMullin, Lowdermilk, James, Mayer, Murphy, Sullivan, Wilkinson; middle row, left to right, Schalk, Jenkins, Felsch, Gleason, E. Collins, J. Collins, Faber, Weaver; front row, left to right, Lynn, Risberg, Leibold, Kerr, McClellan, Williams, Cicotte

Black Sox: Jackson, Gandil, McMullin, Felsch, Weaver, Risberg, Williams, Cicotte

Reds bench at Redland Field before one of the World Series games in 1919, an undated photograph showing the routine proximity of players and fans at ballparks.

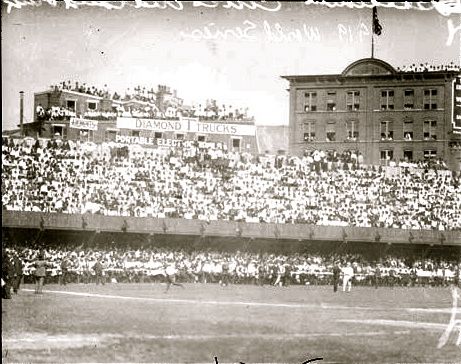

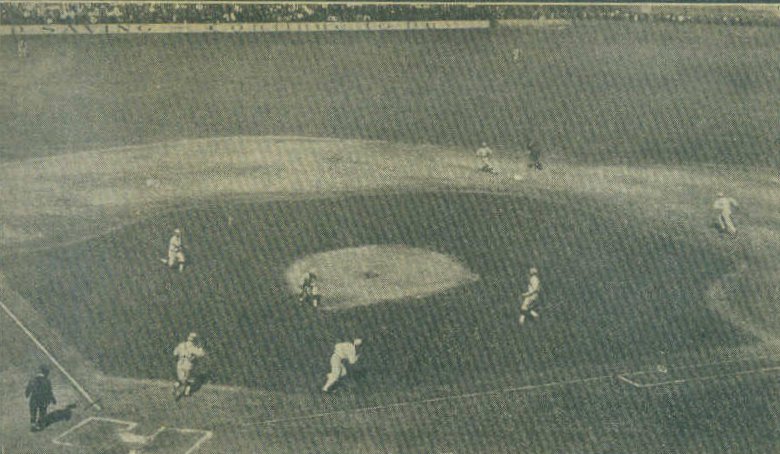

Overflow crowd at Redland Field for Game One, 10/1/1919.

Overflow crowd at Redland Field for Game One, 10/1/1919.

Crowd in downtown Cincinnati listens to Game One updates, 10/1/1919. Mars needs women...

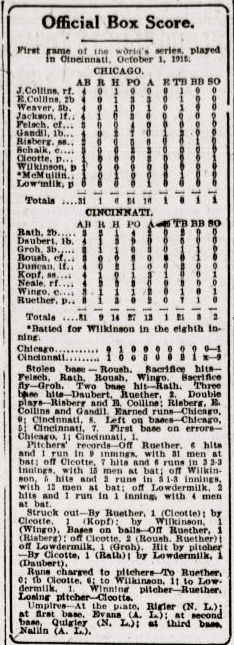

Game One Box Score, New York Sun, 10/2/1919. On the day of the game, the New York Times reported that "every inch of available room in Cincinnati has been taken, and the thousands of fans who arrived late in the afternoon and early last evening found it impossible to find sleeping space." In response, the city had issued an order allowing those with tickets to sleep in the ballpark and had increased police patrols there to protect them "from thieves." Among the more than 30,000 who attended the game (Redland Field had been built to hold just over 20,000), a delegation of Cuban sportswriters had come to report Luque's exploits for the Havana newspapers. In the event, Ruether pitched a complete game, the Reds won 9-1, and the shock of total victory overcame Joseph Pugh, the former Covington police chief, who died shortly after the game of a heart attack "superinduced by the excitement of the afternoon." If anyone had bet on Cicotte to give up six runs on any days other than July 29, August 14, or October 1, 1919, they would have lost their bet.

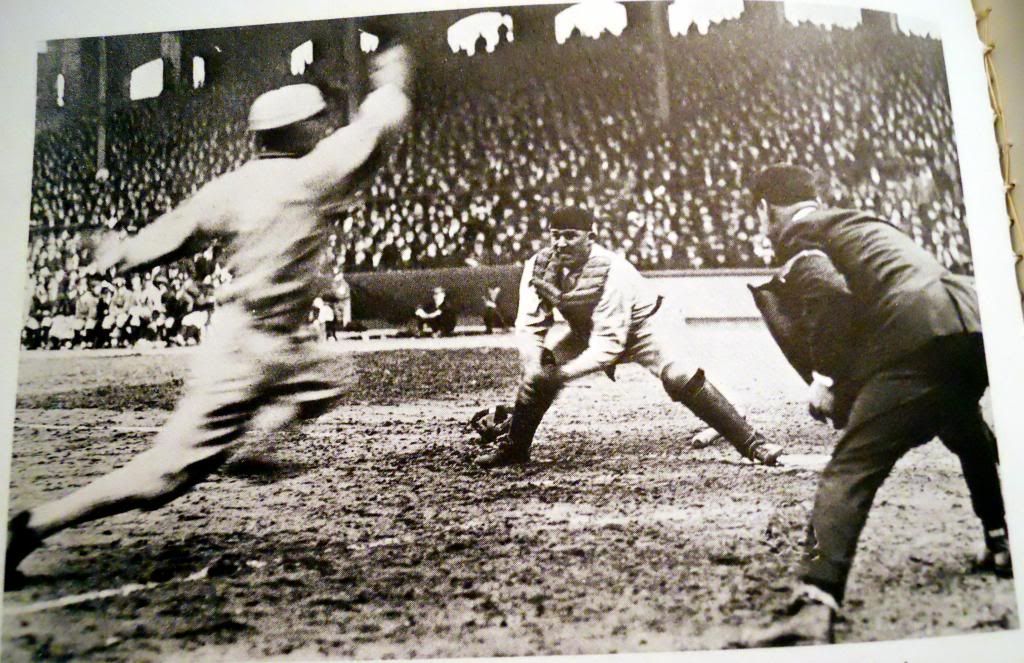

Game Two, Redland Field, 4th inning of a 4-2 Reds win: Buck Weaver makes the second out at home on a fielder's choice from first base, as Bill Rariden applies the tag, and umpire Bill Evans gets ready to make the call. Rariden had also played for the New York Giants in the 1917 World Series, won by the White Sox, 4-2. He came to the Reds in 1919 as part of a trade for Hal Chase, who would figure indirectly in the Black Sox scandal. A great defensive player in his day, Rariden threw out 44% of would-be base stealers over a 12-year career in the National and Federal Leagues.

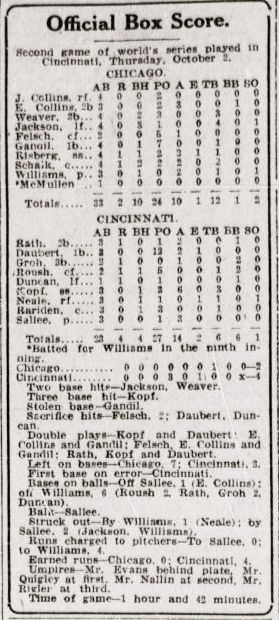

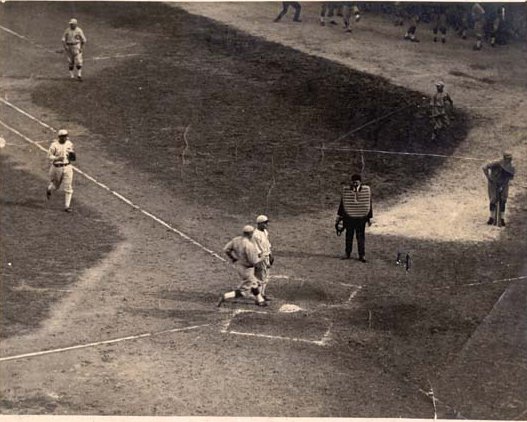

Game Two Box Score, New York Sun, 10/3/1919.

On October 3 in Chicago, Game Three was a closely pitched affair that turned on Cincinnati's defensive mistakes early in the game. Here Reds' starting pitcher Ray Fisher has just fielded Felsch's bunt in the bottom of the second inning and has a play on Jackson at second base. Unfortunately for the Reds, Fisher is also about to throw the ball into the outfield, an error that would put runners on second and third with no outs, setting up...

...Gandil's two-run single to right through the drawn-in infield on the next pitch, Jackson and Felsch both scoring for a 2-0 lead. Kerr wouldn't need any more runs.

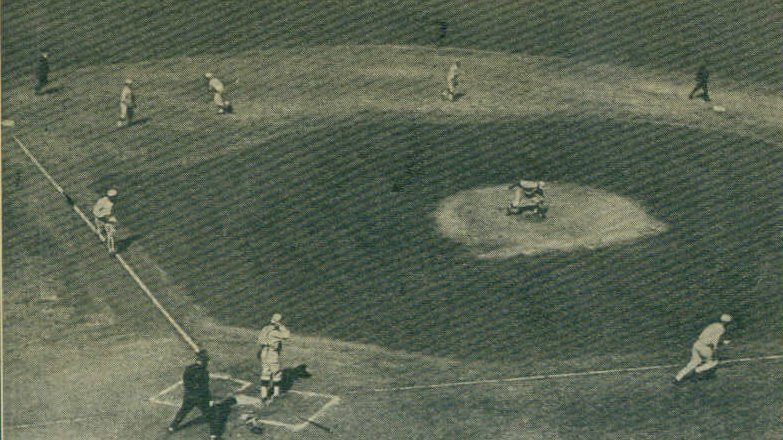

Game Three Box Score, New York Sun, 10/4/1919. Dickie Kerr nursed his own grudge over baseball's labor relations in 1919 but pitched the White Sox to two of their three victories in the Series, including Game Three, a 3-0 Chicago win and complete game three-hitter for Kerr, a lefty control pitcher. Kerr responded to his financial grievances by simply quitting the White Sox in 1922. Much like the Reds he pitched against, Kerr's achievement in 1919 would be overshadowed by his teammates' decision to lose the Series for money.

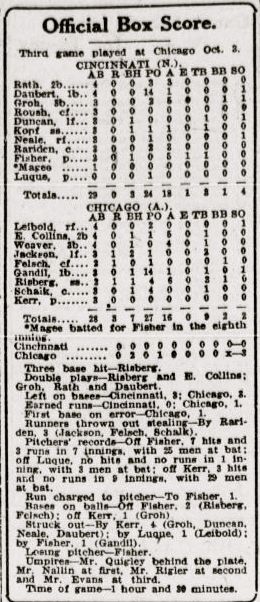

One of the important plays in analyses of the Black Sox scandal: Game 4 in Chicago, 5th inning. As part of the game-deciding sequence, Ed Cicotte's throwing error on Pat Duncan's ground ball back to the mound had put a runner on second with one out. Larry Kopf then singled to left. Joe Jackson threw home for a play on Duncan at the plate, but Cicotte "accidentally" kicked the ball away from catcher Ray Schalk. Cicotte is shown here standing by home plate as Duncan scores. Kopf, who had taken second when the ball went to the screen, scored later in the inning, and the Reds won 2-0 on the strength of these unearned runs. In a 1920 column for the Chicago Tribune, umpire Bill Evans, who worked second base during the game, would write of his disbelief that the ordinarily graceful Cicotte could make such a clumsy mistake...

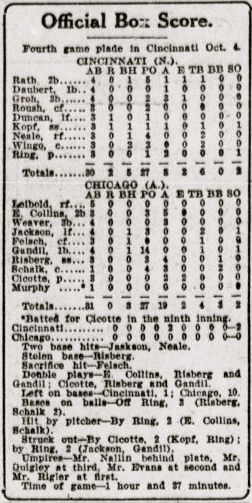

Game Four Box Score, New York Sun, 10/5/1919, incorrectly states that the game was played in Cincinnati.

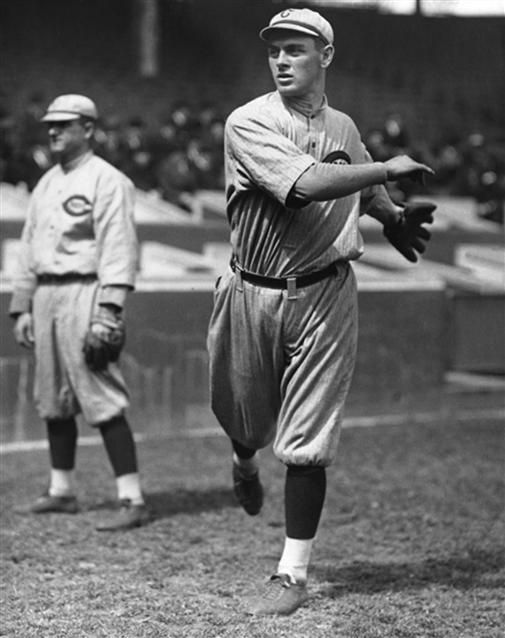

Game Five turned Comiskey Park into a showcase for Hod Eller's brilliant 1919 season (19-9, 2.39, 1.071 whip), which had included a no-hitter (three walks) against the St. Louis Cardinals on May 11. Less than a year later, Eller's career itself would become part of the museum of pitches banned from Major League baseball before the 1920 season. Eller specialized in what he termed a "shine ball," one of the scores of Ty Cobb's "freak pitches" that flourished between roughly 1902 and the 1920 ban, contributing as much as any other factor to the diminished offense of the era. In a 1920 interview, Eller described his pitch as follows: "The shine ball was useless unless thrown with considerable speed. It depended entirely upon smoothing a surface on one side of the ball. Most players used paraffin or some similar substance to smooth the ball. But this was not necessary; merely rubbing the ball vigorously would suffice, if you could put enough speed behind it, and I was usually able to do that. A properly shined ball could be made to break in various ways, but the common way was to make it break up; that is, to give it all the effectiveness of a fastball with compound interest added. To make the ball break up, I used to hold it so that the shiny spot was on top of the ball. The ball would then rise when it crossed the plate fully three or four inches, a much greater break than you could get on a ball from speed alone. But its other break, that is, to one side, was entirely contrary to the similar break of a fastball. One of my fastballs would rise perhaps an inch and break toward a right-handed batter perhaps three or four inches, but a shine ball, held as I have described, would rise at least three or four inches and break away from the batter perhaps five or six." In other words, this was a fastball with extraordinary and unusual movement. Eller was not included on the list of those exempted from the 1920 ban (technically, he didn't throw a spitball), and it effectively ended his pitching career. He left the Major Leagues at the age of 27 after an ineffectual 1921 campaign, arguing that the new rule had deprived him of his livelihood. Clean balls killed Hod Eller...

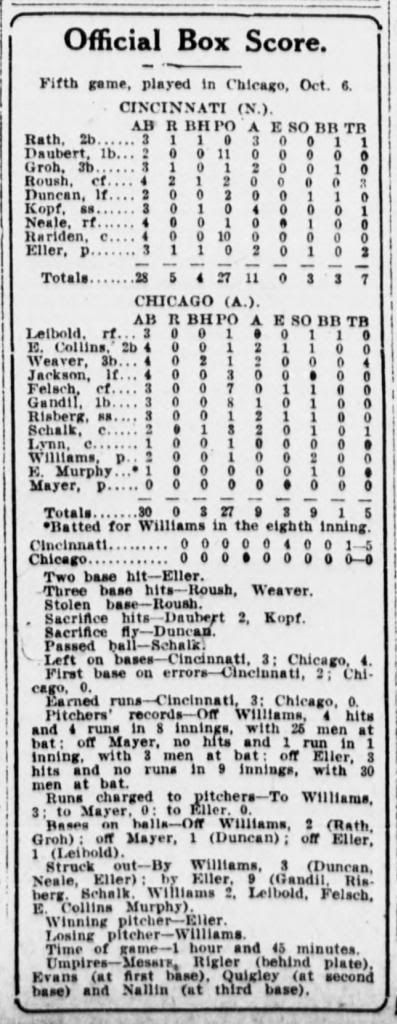

Game Five Box Score, New York Sun, 10/7/1919: the 5-0 win gave the Reds a 4-1 lead in the best-of-nine series. Eller struck out the side in the second and third innings (Gandil, Risberg, Schalk, Williams, Leibold, Collins), setting a World Series record for consecutive strikeouts (another achievement stained by the fix) that would stand until the Orioles' Moe Drabowsky tied it during a 1966 relief appearance. Eller also doubled off Lefty Williams and scored a run in the Reds' four-run sixth inning.

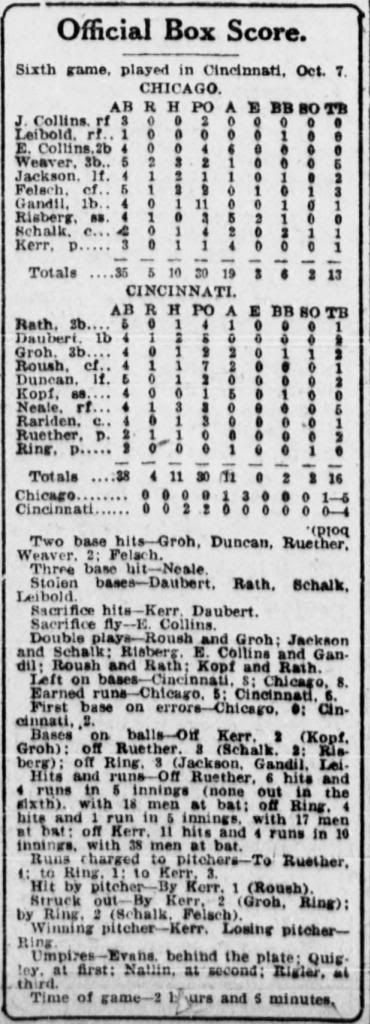

Game Six Box Score, New York Sun, 10/7/1919. Reds had a lead in this one: the most closely balanced offensive contest of the Series and its only extra-inning game. In a decision that hasn’t been questioned, Moran elected to use Ring on short rest (following a complete-game victory in Game Four, three days earlier) over his other relief options (i.e. Luque, who hadn’t pitched in four days: this board would have gone crazy). Though nominally only giving up one run over five relief innings, Ring did blow the save in the sixth and lost the game in the tenth. In a decision that has been much-questioned, Moran elected not to pinch-hit for Ring the rest of the way, even with two on and two out in the bottom of the eighth. Gandil drove in the White Sox' winning run in the tenth and once again appeared to be “trying to win” at least a little bit…

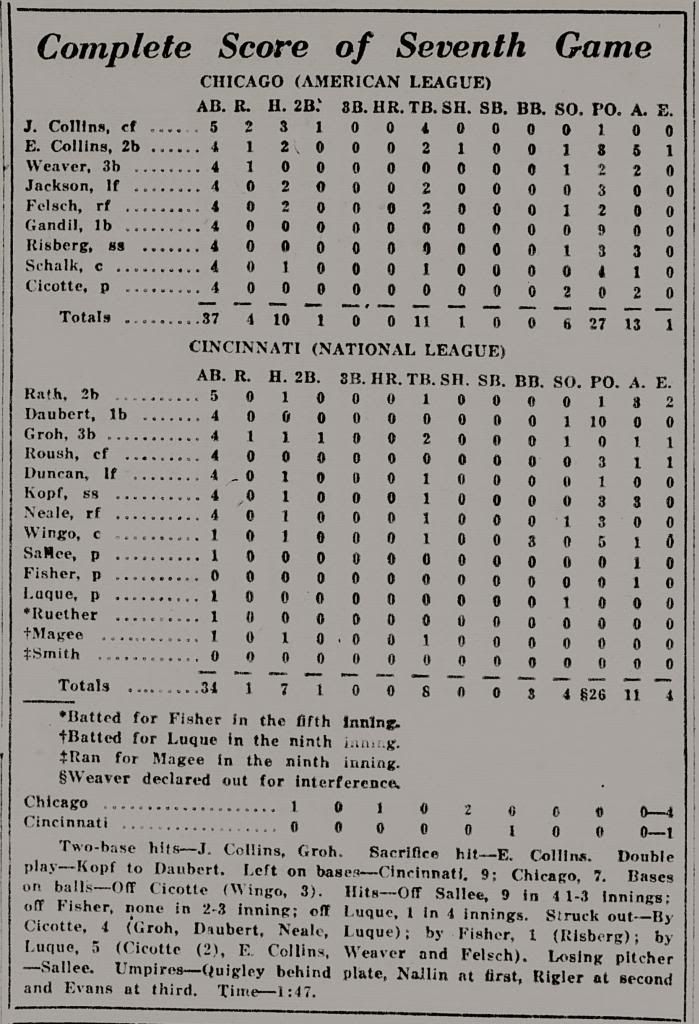

Game Seven Box Score, New York Tribune, 10/9/1919. This 4-1 White Sox victory figured heavily in Black Sox mythology as the only Series game in which the Sox played as a team to win. Hugh Fullerton, in particular, made this a major theme of his writing about the Series. To Fullerton, a Chicago reporter, one of the founders of the Baseball Writers Association of America in 1908, the White Sox could not have lost a Series against the Reds in a fair competition, and Cicotte's Game Seven performance became his evidence. Luque pitched four innings of one-hit, scoreless relief for the Redlegs, who could have won with this in Game Six...

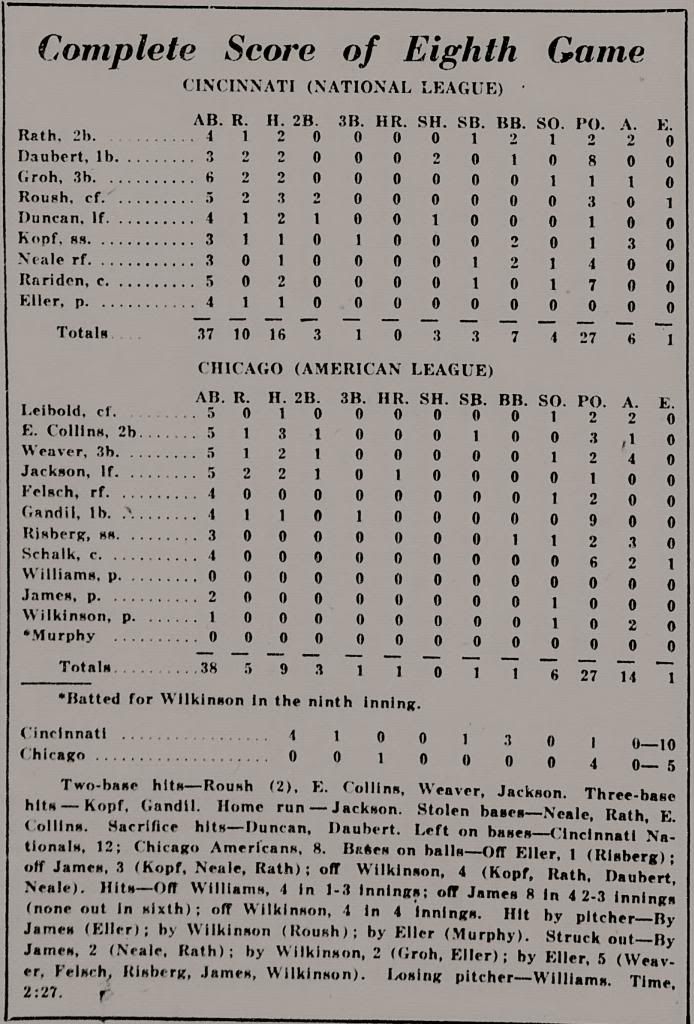

Game Eight Box Score, New York Tribune, 10/10/1919. The clinching game in Chicago involved more suspense than the final score indicates. After the Reds opened the game with four runs on five hits to chase Williams (run-scoring doubles by Roush and Duncan and an rbi single by Rariden), Eller gave up a single and a double to start the bottom of the first. He then struck out Weaver, managed Jackson on an infield popup, and struck out Felsch to strand the runners and hold the lead. Including his Game Five gem, Eller gave up one run over sixteen innings before the White Sox rose up against the nine-run lead in the eighth inning. Joe Jackson hit the only home run of the Series and contributed a two-run double to the eighth-inning rally in his last Series game...

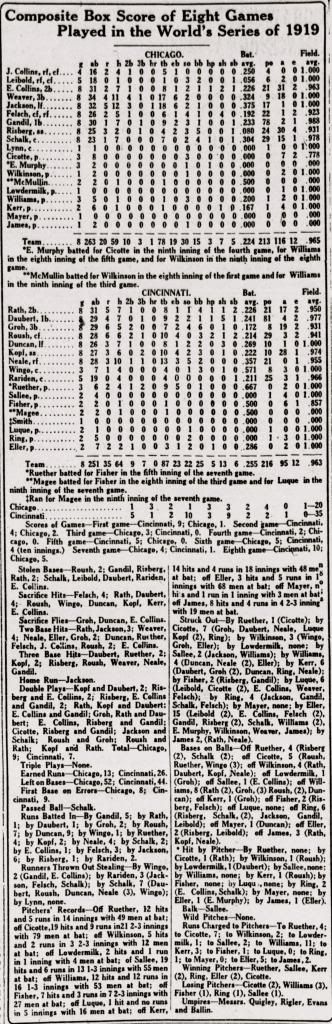

1919 World Series Composite Box Score, New York Sun, 10/10/1919.

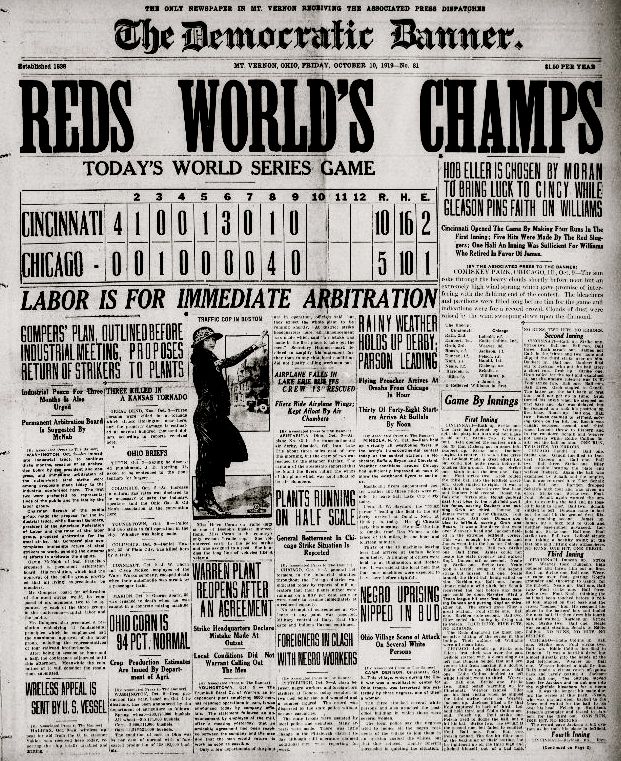

In Mt. Vernon, northern Ohio, news of the Reds' first championship trumped local reports of a racial uprising in the Democratic Banner for October 10, 1919.

Opening Day, April 14, 1920, perhaps 24,000 fans crowded into Redland Field to see the Reds raise their NL Championship and World's Championship banners from the 1919 season. Although newspaper columns by Hugh Fullerton and others had continued to call attention to baseball's gambling problem in general and to doubts about the integrity of the 1919 Series in particular, the Black Sox confessions and indictments that would render the meaning of the Series permanently ambiguous were still months away. Nevertheless, no great record of civic celebration has survived, beyond simply recording the moment. This may reflect the mere accident of records, or it may have resulted from the conviction, firmly established in many quarters by the end of the 1921 season, that victory in the 1919 Series had brought credit to neither the club nor the city, indeed had profited only gamblers and had served only the interests of vice and corruption. From this perspective, those who had beaten the fixers, or who had competed in spite of them, like Kerr, though not in league with organized crime, had unwittingly furthered its interests nonetheless. Newspaper accounts of the Black Sox trial bestowed great powers on the fixers: it was the Black Sox who had decided winners and losers. Under these circumstances, if the play of opponents and teammates deserved no censure, it just as surely did not merit commemoration. The power of this idea did not diminish over time. In the second part of The Godfather, it is one of the gamblers who envisions a statue devoted to the memory of Arnold Rothstein’s ingenious design to fix the Series in 1919…

If reactions to the Black Sox scandal, then and later, conflated winners and losers in this way, what does the 1919 World Series mean across a distance of 94 years? One important aspect of this history concerns what might be described as the social history of trust in modern America. Baseball symbolized (and still symbolizes) innocence in American culture, and the World Series serves as the highest expression of this implicit trust in the virtue of open competition. After its gross betrayal of trust in 1919, the White Sox clubhouse disintegrated into suspicious factions and mutual recriminations late in the 1920 season: the club came in second that year, began to lose players, and never finished better than fifth over the next fifteen years. In turn, Major League Baseball owners, accepting the verdict on the fix as the betrayal of a public trust, undertook radical reforms of their own governing structure in 1920, establishing the office of Commissioner in order to restore public faith in their product, the game on the field...

All this does little to restore meaning to the games of the 1919 Series themselves, save perhaps as cautionary tales about the power of greed, the social rot that follows organized crime, or the evils of labor exploitation. We should therefore end by considering briefly, in a general way, whether these games still hold any value or even interest as baseball games. First, we ought to set aside the mythology of Game Seven: the Black Sox clearly did not decide who won and who lost the Series. If the games were not the spectacle of skill and chance that had defined appreciation of baseball since the 1840s, neither were they the “hippodrome” of scripted circus events. Reality lay between these poles, and one of the unconsidered meanings of the 1919 games concerns their evidence of the difficulty, perhaps the impossibility, of controlling the flow of events on a baseball field…

Christy Mathewson, the former New York Giants pitcher who reported the Series for the New York Times, maintained that crooked players, even pitchers, could have only a limited impact on the final results of games, the scale of events defying individual control. This perspective, from one who, unlike Hugh Fullerton, had played and managed the game at the highest level, helps to dispel some of the Game Seven mythology and brings new meaning to all eight Series games. After all, Sallee had given up ten hits in Game Two as well as in Game Seven. He won the first, 4-2, and lost the second, 4-1. Eller baffled White Sox hitters for most of Game Eight as well as Game Five. Viewed in this way, Fullerton’s belief that the White Sox needed only to play in order to win becomes simply unpersuasive. All claims about game results that "might have been" remain purely speculative, ahistorical, and often contrary to the existing historical record of the games. Not least among its consequences, the fix may well have deprived a public still beset by the grief of war and epidemic of even the minor consolations that one of the great early World Series contests might have provided…